I’ve been thinking about a pattern that keeps repeating throughout history, and we’re about to watch it play out again—this time at digital speed.

The UNDP report on AI adoption in Asia-Pacific isn’t just another development agency white paper. It’s a mirror held up to a region where the future is arriving unevenly, and the reflection should make us deeply uncomfortable.

The Numbers Tell a Story We’ve Seen Before

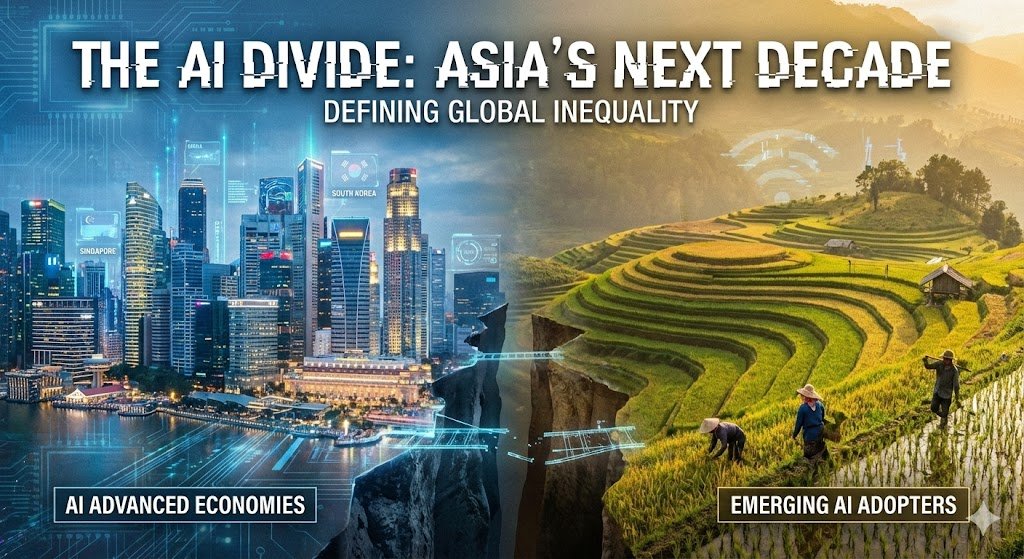

Let me put this in perspective: Afghanistan’s average income is 200 times lower than Singapore’s. Not 2x. Not 20x. Two hundred times.

Now overlay that with this reality: China holds nearly 70% of global AI patents. Singapore, South Korea, and China are investing billions in AI infrastructure while Cambodia, Papua New Guinea, and Vietnam are still figuring out how to get reliable internet to their farmers and frontline health workers.

This isn’t a gap. It’s a chasm that’s about to become a canyon.

The $1 Trillion Question

Here’s what keeps me up at night about the UNDP’s findings: AI is expected to inject nearly $1 trillion in economic gains across Asia over the next decade. That sounds like a win, doesn’t it?

But here’s the question nobody wants to answer clearly: $1 trillion to whom?

When they say AI could lift annual GDP growth by two percentage points and raise productivity by up to 5% in sectors like health and finance, they’re describing an average. Averages are comfortable lies we tell ourselves about deeply uneven distributions.

The uncomfortable truth? That trillion dollars will flow overwhelmingly to countries already positioned to capture it—those with infrastructure, skilled workforces, computing power, and governance systems built for the AI era. The rest will watch the gains accumulate elsewhere while grappling with the costs: job displacement, data exclusion, and the indirect burden of rising global energy and water demands from AI systems they don’t even benefit from.

The Wahyd Paradox

This brings me to platforms like Wahyd Logistics, which I wrote about earlier with genuine enthusiasm. Their AI-powered route optimization, intelligent load matching, and predictive analytics represent exactly the kind of efficiency gains that can transform an industry.

But let’s sit with an uncomfortable question: Who benefits when logistics gets smarter?

If you’re a mid-sized logistics operator in Singapore or Bangkok with decent infrastructure and access to technology platforms, Wahyd’s AI tools are a competitive weapon. You can optimize routes, reduce empty miles, predict disruptions, and operate at margins your competitors can’t match.

If you’re a small trucking operation in rural Cambodia running three aging vehicles with spotty mobile coverage, what exactly does AI-powered logistics do for you? The sophisticated matching algorithms can’t help if you’re not on the platform. The predictive routing is irrelevant if you can’t afford the sensors and connectivity it requires. The efficiency gains accrue to those already efficient enough to access the technology.

This is the paradox of digital transformation in unequal societies: the tools that could theoretically lift everyone often end up concentrating advantages among those already advantaged.

Why This Time Feels Different (And Worse)

Philip Schellekens, UNDP’s Chief Economist for Asia-Pacific, compared this moment to 19th-century industrialization, which “split the world into a wealthy few and the impoverished.”

The comparison is apt, but I think this is actually more dangerous.

Industrial transformation took decades. It gave societies time—however painful—to adapt. Workers could retrain. Governments could develop policies. Education systems could evolve. The pace was brutal, but it was human-scale.

AI transformation is happening at machine speed. An algorithm that automates data entry doesn’t take 20 years to roll out; it takes 20 months, or 20 weeks. The adaptive capacity of institutions—education systems, labor markets, regulatory frameworks—simply can’t keep pace.

And here’s the kicker: during industrialization, at least the factories were geographically distributed. You needed to build them where workers were. With AI, the value creation can happen entirely in Singapore or Shenzhen while the job displacement happens in Manila or Dhaka.

The Women and Youth Problem

The UNDP specifically flags that women and young adults face the biggest threat from AI in the workplace. This deserves unpacking.

Entry-level positions—the traditional gateway to economic mobility—are disproportionately at risk. Customer service, data entry, basic bookkeeping, routine administrative work: these are exactly the jobs that AI automates most easily, and they’re exactly the jobs where young people gain initial work experience and where women in many Asian societies find entry points into the formal economy.

When Wahyd implements an AI chatbot to handle shipment tracking queries—a genuinely smart efficiency move—someone’s first job disappears. Multiply that across every sector where AI can automate routine cognitive tasks, and you have an entire generation whose pathway to economic participation is being redesigned without their input.

The cruel irony? The countries with the weakest social safety nets, the fewest retraining programs, and the most precarious labor markets are the ones where this displacement will hit hardest.

What “Inclusive” AI Actually Requires

The UNDP calls for governments to “ensure AI is rolled out in as inclusive a way as possible.” I appreciate the sentiment, but I’m skeptical about the execution.

Inclusive AI isn’t about making sure everyone has a chatbot. It’s about fundamentally rethinking how we approach technological transformation in contexts of extreme inequality.

For countries like Cambodia, Papua New Guinea, and Vietnam, the report correctly identifies that the priority isn’t developing cutting-edge AI—it’s deploying simple, voice-based tools that work offline and serve immediate needs. A farmer using a voice assistant to check crop prices or a health worker accessing diagnostic protocols via simple voice queries doesn’t sound as sexy as autonomous vehicles or predictive analytics, but it’s technology appropriate to context.

This matters more than we acknowledge. There’s a tendency—particularly among technologists and policy makers in wealthy nations—to assume every country should follow the same AI adoption trajectory. But the AI that makes sense in Singapore might be irrelevant or even harmful in settings with different infrastructure, literacy rates, and economic structures.

The Governance Gap Nobody Talks About

Here’s a dimension the UNDP touches on but deserves more attention: governance capacity.

Regulating AI requires technical expertise most governments don’t have. It requires the ability to audit algorithms, enforce data protection, prevent discriminatory outcomes, and balance innovation with safeguards. These aren’t trivial capabilities—they’re expensive, specialized, and time-consuming to build.

Wealthy countries struggle with this. How exactly are countries with limited resources supposed to govern AI systems designed and deployed by foreign companies, operating on data they can’t access, using techniques they don’t understand?

The result is predictable: extractive AI. Systems deployed to capture value from developing markets while concentrating benefits elsewhere. Data flows out. Profits flow out. Jobs disappear. And the governance structures to prevent or redirect this simply don’t exist.

The Energy and Water Dimension

The UNDP mentions “rising global energy and water demands from AI-intensive systems” almost as an aside, but this deserves its own spotlight.

Training large AI models consumes enormous amounts of electricity and water (for cooling data centers). This energy demand is met globally, but the costs aren’t distributed evenly. Countries already struggling with power infrastructure and water access are now competing with AI companies for these resources, while receiving little benefit from the AI systems driving demand.

It’s a form of environmental colonialism: the computational power required for AI concentration in wealthy nations creates resource pressure everywhere, but the gains from that computation accrue narrowly.

What Should Actually Happen (But Probably Won’t)

If I were designing policy for Asia-Pacific AI adoption—knowing I’m not, but indulge me—here’s what I’d prioritize:

1. Context-Appropriate Technology First: Stop pushing frontier AI where basic digital infrastructure doesn’t exist. Voice-based tools, offline-capable systems, and technology designed for low-connectivity environments should receive as much investment and attention as generative AI. Unglamorous? Yes. Essential? Absolutely.

2. Regional Data Sovereignty: Countries need frameworks to ensure data generated within their borders creates value within their borders. This isn’t protectionism—it’s preventing the wholesale extraction of the raw material (data) that powers AI while receiving none of the benefits.

3. Massive Investment in Transition Support: The jobs that AI automates aren’t coming back. Governments need to fund—seriously fund, not pilot-program fund—retraining, social safety nets, and alternative economic opportunities. This costs money nobody wants to spend, but the alternative is social instability that costs far more.

4. Mandatory Impact Assessments: Before deploying AI systems at scale, require assessments of employment impact, distributional effects, and alternative approaches. Make it expensive to automate without considering consequences.

5. Tax Automation, Fund People: If AI is generating trillion-dollar gains, tax those gains and redistribute them. Universal basic income, negative income taxes, public employment programs—the mechanism matters less than the principle that the benefits of automation should be shared.

Will any of this happen? Honestly, probably not at the scale and speed required. The political economy of AI favors those with capital and technical capacity. The winners have little incentive to slow down, and the losers have little power to make them.

The Wahyd Opportunity (And Responsibility)

Circling back to Wahyd and similar platforms: they’re not villains in this story. They’re building genuinely useful technology that creates real value.

But they also have choices to make.

They can optimize purely for efficiency and let the distributional consequences fall where they may. Or they can consciously design for inclusion—deliberately ensuring their platforms remain accessible to smaller operators, providing training and support to help less sophisticated users compete, and thinking hard about how their technology reshapes labor markets in the communities where they operate.

The latter is harder and probably less profitable in the short term. But it’s the difference between being another tool of unequal development and being a genuine force for broadly shared prosperity.

I’d like to see Wahyd and others in the logistics space publish regular reports on the employment impact of their platforms. How many jobs are being automated? What new roles are being created? What skills do workers need to transition successfully? What’s the company doing to facilitate that transition?

Transparency doesn’t solve the problem, but it at least makes the problem visible.

A Closing Thought That Won’t Comfort Anyone

Kanni Wignaraja from UNDP said it plainly: “AI is racing ahead, and many countries are still at the starting line.”

That metaphor is precise, but here’s the thing about races: someone wins and someone loses. We’re treating AI adoption as if it’s some neutral process where everyone eventually benefits if they just try hard enough.

But technology doesn’t diffuse in vacuums. It diffuses in societies with existing power structures, inequalities, and dynamics of advantage. AI—like every transformative technology before it—will amplify what’s already there. If you have infrastructure, skills, and capital, AI makes you more productive. If you don’t, AI makes you redundant.

The UNDP’s warning about countries being “left far behind” undersells the problem. They won’t just be left behind—they’ll be actively disadvantaged, competing in global markets against entities with AI-powered productivity they can’t match, while bearing the costs of disruption without the benefits of innovation.

This isn’t inevitable. It’s a choice we’re making collectively—to prioritize innovation speed over distributional fairness, to treat efficiency as the sole metric of success, to assume that markets will somehow sort it all out despite overwhelming evidence that they won’t.

There’s still time to make different choices. But the window is closing fast.

And unlike AI, which gets smarter over time, our institutions for managing technological change seem to be getting slower and less effective just when we need them most.

That should terrify us more than it seems to.

I didn’t want to talk about Wahyd in this. This is a seperate news all together

17:14

The AI Divide: Why Asia’s Next Decade Will Define Global Inequality

I’ve been thinking about a pattern that keeps repeating throughout history, and we’re about to watch it play out again—this time at digital speed.

The UNDP report on AI adoption in Asia-Pacific isn’t just another development agency white paper. It’s a mirror held up to a region where the future is arriving unevenly, and the reflection should make us deeply uncomfortable.

The Numbers Tell a Story We’ve Seen Before

Let me put this in perspective: Afghanistan’s average income is 200 times lower than Singapore’s. Not 2x. Not 20x. Two hundred times.

Now overlay that with this reality: China holds nearly 70% of global AI patents. Singapore, South Korea, and China are investing billions in AI infrastructure while Cambodia, Papua New Guinea, and Vietnam are still figuring out how to get reliable internet to their farmers and frontline health workers.

This isn’t a gap. It’s a chasm that’s about to become a canyon.

The $1 Trillion Question

Here’s what keeps me up at night about the UNDP’s findings: AI is expected to inject nearly $1 trillion in economic gains across Asia over the next decade. That sounds like a win, doesn’t it?

But here’s the question nobody wants to answer clearly: $1 trillion to whom?

When they say AI could lift annual GDP growth by two percentage points and raise productivity by up to 5% in sectors like health and finance, they’re describing an average. Averages are comfortable lies we tell ourselves about deeply uneven distributions.

The uncomfortable truth? That trillion dollars will flow overwhelmingly to countries already positioned to capture it—those with infrastructure, skilled workforces, computing power, and governance systems built for the AI era. The rest will watch the gains accumulate elsewhere while grappling with the costs: job displacement, data exclusion, and the indirect burden of rising global energy and water demands from AI systems they don’t even benefit from.

Why This Time Feels Different (And Worse)

Philip Schellekens, UNDP’s Chief Economist for Asia-Pacific, compared this moment to 19th-century industrialization, which “split the world into a wealthy few and the impoverished.”

The comparison is apt, but I think this is actually more dangerous.

Industrial transformation took decades. It gave societies time—however painful—to adapt. Workers could retrain. Governments could develop policies. Education systems could evolve. The pace was brutal, but it was human-scale.

AI transformation is happening at machine speed. An algorithm that automates data entry doesn’t take 20 years to roll out; it takes 20 months, or 20 weeks. The adaptive capacity of institutions—education systems, labor markets, regulatory frameworks—simply can’t keep pace.

And here’s the kicker: during industrialization, at least the factories were geographically distributed. You needed to build them where workers were. With AI, the value creation can happen entirely in Singapore or Shenzhen while the job displacement happens in Manila or Dhaka.

The wealth doesn’t trickle down when it doesn’t need to be there in the first place.

The Women and Youth Problem Nobody Wants to Face

The UNDP specifically flags that women and young adults face the biggest threat from AI in the workplace. This deserves unpacking because it reveals something structural about how technological disruption compounds existing inequalities.

Entry-level positions—the traditional gateway to economic mobility—are disproportionately at risk. Customer service, data entry, basic bookkeeping, routine administrative work: these are exactly the jobs that AI automates most easily, and they’re exactly the jobs where young people gain initial work experience and where women in many Asian societies find entry points into the formal economy.

Think about what this means practically. A young woman in Manila who might have started her career in business process outsourcing—taking customer service calls, processing insurance claims, managing data—now faces a market where those jobs are being systematically automated. Her educational credentials haven’t changed. Her work ethic hasn’t changed. But the ladder she was supposed to climb is being removed, rung by rung.

The cruel irony? The countries with the weakest social safety nets, the fewest retraining programs, and the most precarious labor markets are the ones where this displacement will hit hardest.

What “Inclusive” AI Actually Requires (And Why We’re Failing)

The UNDP calls for governments to “ensure AI is rolled out in as inclusive a way as possible.” I appreciate the sentiment, but I’m skeptical about the execution because I’ve seen this movie before.

Inclusive AI isn’t about making sure everyone has access to ChatGPT. It’s about fundamentally rethinking how we approach technological transformation in contexts of extreme inequality.

For countries like Cambodia, Papua New Guinea, and Vietnam, the report correctly identifies that the priority isn’t developing cutting-edge AI—it’s deploying simple, voice-based tools that work offline and serve immediate needs. A farmer using a voice assistant to check crop prices or a health worker accessing diagnostic protocols via simple voice queries doesn’t sound as sexy as generative AI or autonomous systems, but it’s technology appropriate to context.

This matters more than we acknowledge. There’s a tendency—particularly among technologists and policy makers in wealthy nations—to assume every country should follow the same AI adoption trajectory. Silicon Valley’s roadmap becomes the world’s roadmap. But the AI that makes sense in Singapore might be irrelevant or even harmful in settings with different infrastructure, literacy rates, and economic structures.

We keep trying to skip steps that can’t be skipped.

The Governance Gap Nobody Talks About

Here’s a dimension the UNDP touches on but deserves more attention: governance capacity.

Regulating AI requires technical expertise most governments don’t have. It requires the ability to audit algorithms, enforce data protection, prevent discriminatory outcomes, and balance innovation with safeguards. These aren’t trivial capabilities—they’re expensive, specialized, and time-consuming to build.

The European Union is struggling to implement the AI Act, and they have resources, technical talent, and institutional capacity. How exactly are countries with limited resources supposed to govern AI systems designed and deployed by foreign companies, operating on data they can’t access, using techniques they don’t understand?

The result is predictable: extractive AI. Systems deployed to capture value from developing markets while concentrating benefits elsewhere. Data flows out. Profits flow out. Jobs disappear. And the governance structures to prevent or redirect this simply don’t exist.

It’s digital colonialism with better branding.

The Energy and Water Dimension We’re Ignoring

The UNDP mentions “rising global energy and water demands from AI-intensive systems” almost as an aside, but this deserves its own spotlight because it reveals the hidden infrastructure of inequality.

Training large AI models consumes enormous amounts of electricity and water (for cooling data centers). A single training run for a large language model can use as much electricity as hundreds of homes consume in a year. The water usage for cooling is staggering—we’re talking millions of gallons.

This energy demand is met globally, but the costs aren’t distributed evenly. Countries already struggling with power infrastructure and water access are now competing with AI companies for these resources, while receiving little benefit from the AI systems driving demand.

Pakistan faces recurring energy crises. Bangladesh struggles with water scarcity. Yet global AI development creates additional pressure on these resources—pressure driven by innovation happening elsewhere, benefiting populations elsewhere, while the environmental and infrastructure costs are socialized globally.

It’s a form of environmental colonialism: the computational power required for AI concentration in wealthy nations creates resource pressure everywhere, but the gains from that computation accrue narrowly.

What Should Actually Happen (But Probably Won’t)

If I were designing policy for Asia-Pacific AI adoption—knowing I’m not, but indulge me—here’s what I’d prioritize:

1. Context-Appropriate Technology First: Stop pushing frontier AI where basic digital infrastructure doesn’t exist. Voice-based tools, offline-capable systems, and technology designed for low-connectivity environments should receive as much investment and attention as generative AI. Unglamorous? Yes. Essential? Absolutely.

2. Regional Data Sovereignty Frameworks: Countries need mechanisms to ensure data generated within their borders creates value within their borders. This isn’t protectionism—it’s preventing the wholesale extraction of the raw material (data) that powers AI while receiving none of the benefits. Think of it as resource nationalism for the digital age.

3. Massive Investment in Transition Support: The jobs that AI automates aren’t coming back. Governments need to fund—seriously fund, not pilot-program fund—retraining, social safety nets, and alternative economic opportunities. This costs money nobody wants to spend, but the alternative is social instability that costs far more.

4. Mandatory Employment Impact Assessments: Before deploying AI systems at scale, require assessments of employment impact, distributional effects, and alternative approaches. Make it expensive to automate without considering consequences. Build friction into the system deliberately.

5. Tax Automation, Fund People: If AI is generating trillion-dollar gains, tax those gains aggressively and redistribute them. Universal basic income, negative income taxes, public employment programs—the mechanism matters less than the principle that the benefits of automation should be shared, not hoarded.

Will any of this happen? Honestly, probably not at the scale and speed required. The political economy of AI favors those with capital and technical capacity. The winners have little incentive to slow down, and the losers have little power to make them.

The Starting Line Metaphor Is Wrong

Kanni Wignaraja from UNDP said it plainly: “AI is racing ahead, and many countries are still at the starting line.”

That metaphor is precise, but here’s the thing about races: someone wins and someone loses. We’re treating AI adoption as if it’s some neutral process where everyone eventually benefits if they just try hard enough.

But technology doesn’t diffuse in vacuums. It diffuses in societies with existing power structures, inequalities, and dynamics of advantage. AI—like every transformative technology before it—will amplify what’s already there. If you have infrastructure, skills, and capital, AI makes you more productive. If you don’t, AI makes you redundant.

The UNDP’s warning about countries being “left far behind” undersells the problem. They won’t just be left behind—they’ll be actively disadvantaged, competing in global markets against entities with AI-powered productivity they can’t match, while bearing the costs of disruption without the benefits of innovation.

Here’s the honest truth: many countries aren’t at the starting line of the same race. They’re running a different race entirely, on a different track, with different obstacles, while being measured against the same finish line.

The Uncomfortable Questions We Need to Ask

So where does this leave us?

I keep coming back to a question that Philip Schellekens implies but doesn’t state directly: Are we watching the deliberate construction of a two-tiered global economy—one where AI-empowered nations operate at unprecedented levels of productivity while AI-displaced nations struggle with unemployment, instability, and irrelevance?

And if so, is this a bug or a feature?

Because here’s what makes me cynical: the system is working exactly as designed. Capital flows to where returns are highest. Innovation concentrates where infrastructure and talent cluster. Markets don’t optimize for equity; they optimize for efficiency. And efficiency, in this case, means automating expensive labor and concentrating gains among those who own the technology.

The rhetoric about “inclusive AI” and “leaving no one behind” is comforting, but it runs counter to every economic incentive actually driving AI development and deployment.

A Closing Thought That Won’t Comfort Anyone

This isn’t inevitable. It’s a choice we’re making collectively—to prioritize innovation speed over distributional fairness, to treat efficiency as the sole metric of success, to assume that markets will somehow sort it all out despite overwhelming evidence that they won’t.

There’s still time to make different choices. But the window is closing fast, and I see little evidence of the political will required to force course corrections.

The UNDP report is a warning. Whether anyone with power to act is listening remains to be seen.

What I know is this: in ten years, we’ll look back at this moment and either marvel at how we managed to navigate technological transformation with some degree of equity and foresight, or we’ll catalog it as another chapter in the long history of innovation that enriched the few while disrupting the many.

The Asia-Pacific region—home to 55% of the world’s population—will be where that story is written most dramatically.

And unlike AI, which gets smarter over time, our institutions for managing technological change seem to be getting slower and less effective just when we need them most.

That should terrify us more than it seems to.